Why AI agents need to learn to read the room

The social expectations we project onto AI

If an AI agent behaves consistently across all channels, it will feel more reliable to the end user, right?

On the surface, that makes sense.

But imagine someone who speaks the same way to everyone, regardless of setting. They’re using the same tone at a funeral as they would at a bar. Technically consistent, socially off.

As AI moves across chat, email, voice and WhatsApp, that same tension becomes visible. Different channels carry very different social expectations. People arrive with different levels of patience, different ideas of formality, and different assumptions about who, or what, is on the other side.

In our research, what stood out most wasn’t always whether the AI was accurate, but whether the response fit the moment. Behaviour that felt efficient in chat could feel dismissive in email. A conversational tone that built rapport on the phone could feel out of place when written down.

In other words, trust wasn’t shaped by consistency alone. It was shaped by our own social expectations when it comes to communication.

This reframing helped explain a pattern we kept seeing across channels: When interactions felt wrong, users didn’t blame the answer. They questioned the system’s understanding. And once that doubt set in, every subsequent response was judged more harshly.

From there, the question shifted. Not how consistent should an AI be, but where consistency helps, and where it can misalign with social expectations.

The anthropology of digital channels

Every communication channel comes with a social contract that’s been shaped long before AI arrived.

Chat interfaces signal speed and informality. Email signals deliberation and record-keeping. Voice carries decades of conversational norms around turn-taking, pacing, and politeness. Messaging platforms sit somewhere in between, blending immediacy with continuity.

These signals shape behaviour automatically. People skim in chat. They write carefully in email. They speak differently on the phone than they type on a screen.

When AI responses align with those expectations, interactions feel natural. When they don’t, even small deviations stand out.

What surfaced in Messenger

Messenger is where end users behave in the most AI-compatible way: quickly, casually, and without ceremony. The mental model is transactional:

Type → Get → Move on.

Messenger revealed how closely trust is tied to cognitive effort.

We conducted concept testing with more than 100 end users to understand how different interactional features influenced their experience of AI conversations. We explored preferences around concise responses, empathy, collaboration, and personalisation.

To validate these findings, we applied a controlled model to thousands of real Fin conversations, measuring the statistical impact of each feature on CSAT and resolution outcomes. Here’s what we found.

Chunking information

On chat, users are skim-reading. A long paragraph can come across as a burden instead of thorough.

Clarity and structure reduced friction more than completeness. Bullet points, short paragraphs, and clear structure helped people quickly understand what mattered and what to do next. A more conversational approach, including the ability to redirect the conversation by asking a follow-up, clarifying intent, or changing course was more valuable than receiving a fully comprehensive answer upfront.

Empathy, personalisation, and naturalness

We tested the statistical significance of these traits on Customer Satisfaction and found that end users want to be heard, reassured and to feel like the AI is working with them to solve their issue.

The design challenge is not just accuracy, it’s also cognitive ease. Fin on Messenger must be concise by default, empathetic to an extent and personalise the answer to the customer.

Fin now uses more natural, context-appropriate language—reducing verbosity while expressing empathy where it matters. Since these changes, we’ve seen higher CSAT and a meaningful increase in hard resolutions across conversations.

What surfaced in email

Email exposed a very different set of expectations.

People wrote emails more deliberately. They invested time in explaining context, describing edge cases, composing something “for the record”, especially when:

The issue is complex,

The stakes are high,

They want a “real person”

In this context, extremely fast and concise replies sometimes created uncertainty about how much attention had been given to the issue.

The formality expectation

On email, users expect a greeting, acknowledgment of the problem, a structured solution, and a sign-off. When Fin responds like a chat agent, users describe it as dismissive or even rude.

The quality expectation

Most email queries are inherently more complex than chat messages. Many require actions: refunds, adjustments, account checks. Therefore more information-dense answers are expected.

The identity expectation

Crucially, people do not expect AI in their inbox. They assume every email they receive is written by a human. This makes tone, accuracy, and personalisation far more consequential. A small mistake feels bigger. A generic sentence feels colder.

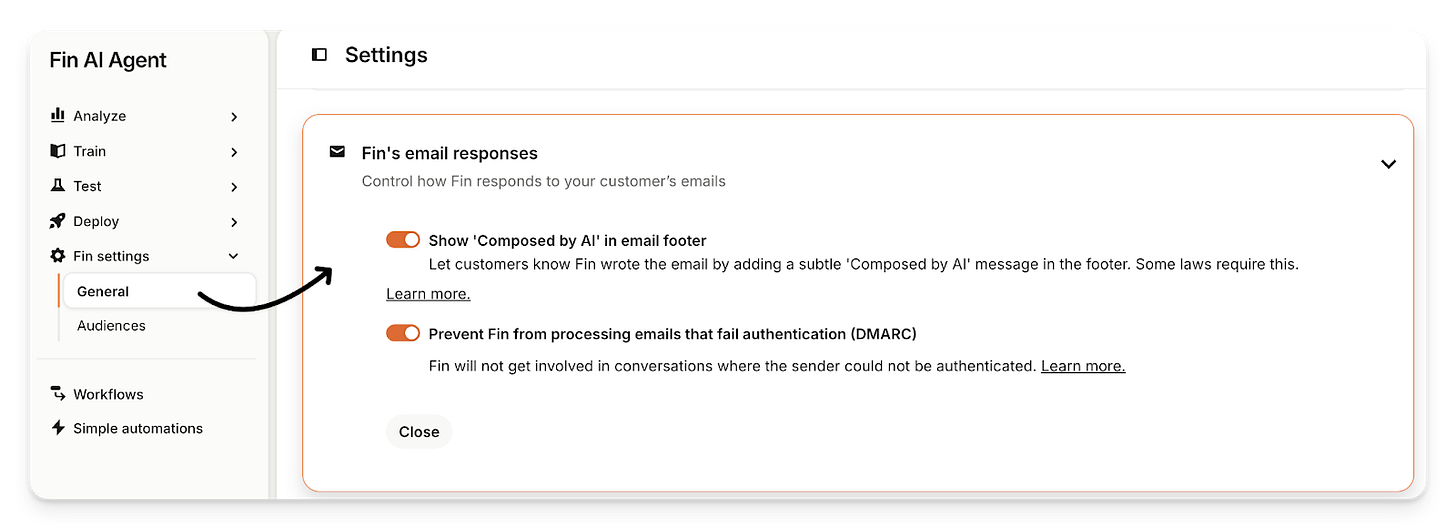

With Fin, customers can add an introductory message at the start of the AI agent’s first reply in the email conversation

They can also choose to display an “AI agent” footer directly below the AI agent’s Signature on every email

What surfaced in voice interactions

Voice is the channel where expectations are most deeply ingrained. Interactions are personal, and we bring decades of conversational instinct with us: how to take turns, when to interrupt, how to signal frustration, how to tell if someone is listening.

These norms are so automatic that users don’t consciously adjust them. That is until something feels off…

Early interactions with Fin Voice were often surprisingly positive. Users came in expecting a rigid, button-pushing system. When Fin responded conversationally, understood intent, and moved quickly, trust spiked. But that trust was conditional.

The moment Fin sounded robotic, or lacked social graces (e.g. hanging up without saying goodbye), users recalibrated - not just in their opinion of Fin, but their own behaviour.

They stopped elaborating.

They shortened their sentences.

They waited passively instead of interrupting.

“If it answers too fast, it feels fake. If it waits too long, I think it’s broken.”

- End user quote

Even when Fin could be interrupted, users didn’t try. The voice sounded like a machine, so they treated it like one.

This is the hidden challenge of voice AI: Perceived limitations shape interaction more than actual ones.

When users believe they’re talking to a bot, they begin mimicking bot behaviour. They simplify language. They avoid nuance. They withhold emotion. And in doing so, they make the system less effective.

This in turn confirms their original assumption that “the bot won’t understand anyway.”

We are intentionally designing Fin Voice with social norms in mind; optimising conversational flow to ensure pacing, clarification, follow-ups, and tone align with how people expect phone conversations to work.

What surfaced in WhatsApp

WhatsApp introduced a different kind of pressure.

Unlike chat widgets that signal a bounded support interaction, WhatsApp feels personal and continuous. Conversations don’t clearly start or end; they pause and resume. Messages arrive alongside family updates, work threads, and voice notes from friends. That context shaped how AI responses were judged.

Speed mattered, but not in the same way as chat. A delayed response on WhatsApp felt less like waiting in a queue and more like being ignored. Gaps in the conversation carried emotional weight, even when expectations around resolution time were technically reasonable.

Continuity mattered just as much. Users expected the conversation to pick up where it left off, without re-establishing context or repeating details.

Tone also landed differently. Informality was expected, but so was relevance. Messages that felt templated or disconnected from the ongoing thread stood out immediately.

On WhatsApp, trust was shaped by presence. Being responsive, context-aware, and able to resume the conversation naturally mattered more than perfect phrasing.

The pattern across channels

Across every environment, certain qualities consistently shaped trust:

Responses that acknowledged context

Clarity that reduced effort

Tone that matched the seriousness of the situation

Speed that feels appropriate to the situation

But each channel weighs these differently.

The goal is to ensure the experience aligns with what end users expect from the channel they’re using.

Rethinking consistency

Consistency still matters, but not in the way it’s often defined.

What users seemed to respond to wasn’t identical behaviour everywhere, but a sense that the system understood where it was operating. That it respected the social-norms of the medium.

When behaviour felt appropriate, users focused on solving their problem. When it didn’t, they focused on the competence of the system itself.

That difference between usefulness and self-consciousness is where trust is either built or lost.

These observations don’t point to more personality, or less automation. They point to something simpler and harder to design for: context.

As AI continues to move across surfaces, the question isn’t whether it should behave consistently.

It’s whether it can recognise the room it’s in.