To Vibe Code, or Not to Vibe Code?

From Ambiguity to Impact: Using AI as a Design Lever

There’s a particular kind of product failure that’s especially painful—not because it’s dramatic, but because it unfolds slowly.

Many moons ago, my team worked on a concept for a new Intercom ML feature that, on paper, seemed genuinely valuable. The idea was to mine historical conversations to identify recurring processes or sequences of actions agents had taken to resolve similar issues in the past.

From there, we’d standardize those patterns into a kind of game plan, so when an inexperienced agent encountered a similar situation, the system could recognize what they were trying to do and suggest the next best action.

To explore this, we invested heavily in the underlying ML technology. We also designed simple front-end representations of how this might show up for agents. But as the work progressed, I started to feel uneasy. The further we progressed, the more it seemed true value hinged on inaccessible data and speculative, high-investment tech.

Rather than continuing down that path, I wanted to force a gut-check.

Once we had a system capable of pulling real customer data, I pushed to get a realistic version of the experience in front of potential users. Not because I was confident it would succeed—but because I was worried it wouldn’t, and I wanted an answer before we sank more time into it.

That feedback made the risk unmistakable. The path to real value was long and uncertain. The experience, as we could realistically build it, wasn’t landing strongly enough to justify what would come next.

We killed the idea.

What stays with me isn’t that we stopped, but how much work it took to reach that conclusion. We didn’t need a perfect system. We just needed something real enough for users to react to, something that let them explore their data and show us whether our intended value was within reach.

Looking back, it’s hard not to think: if vibe coding had existed then, this would have been a perfect opportunity for it.

What Vibe Coding Is (And Isn’t)

Before going further, it’s worth being clear about what I mean by “vibe coding.”

By vibe coding, I mean using AI tools to generate executable prototypes quickly and explore full user journeys, interactions, motion, and realistic data in a way that static design tools struggle to support. It’s low-confidence and low-fidelity on most axes, and high-fidelity on only the elements that matter.

I’m not talking about making architectural decisions, writing production-ready code, or using coding agents to make small fixes directly in live systems. That’s a real and useful practice, but it’s not what this post is about. Here, I consider vibe coding to be an exploratory design mode.

When designers talk about vibe coding, the conversation tends to swing between two extremes. On one side, there’s hype.

“Everyone should be doing this all the time.”

On the other, fear.

“It’s sloppy, it erodes craft. It makes designers lazy, or worse, unnecessary.”

That anxiety is understandable. When tools make it easier for anyone to create executable prototypes, it’s natural to wonder what unique value design still brings. But framing the question that way misses the point.

I’ve found the value of vibe coding isn’t speed. It’s not about replacing Figma, skipping rigor, or racing to ship. And it’s not about who can build prototypes. It’s about who knows when making something real is the right move, and what to do with the clarity that follows.

Vibe coding isn’t really about speed—it’s about alignment.

Alignment on whether something is actually valuable, or just impressive. Alignment on whether something is truly feasible, or should be stripped back. Vibe coding works because it turns abstract disagreement into something experiential. It gives teams something real to react to instead of something imaginary to argue about.

Vibe coding makes ideas real faster, which means it amplifies potential, but it also amplifies risk. Vibe coding amplifies everything. Weak ideas don’t quietly fade away; they get louder. Gaps become obvious. That’s not a downside; it’s the point.

An Emerging Design Skill: Using Vibe Coding as a Mode

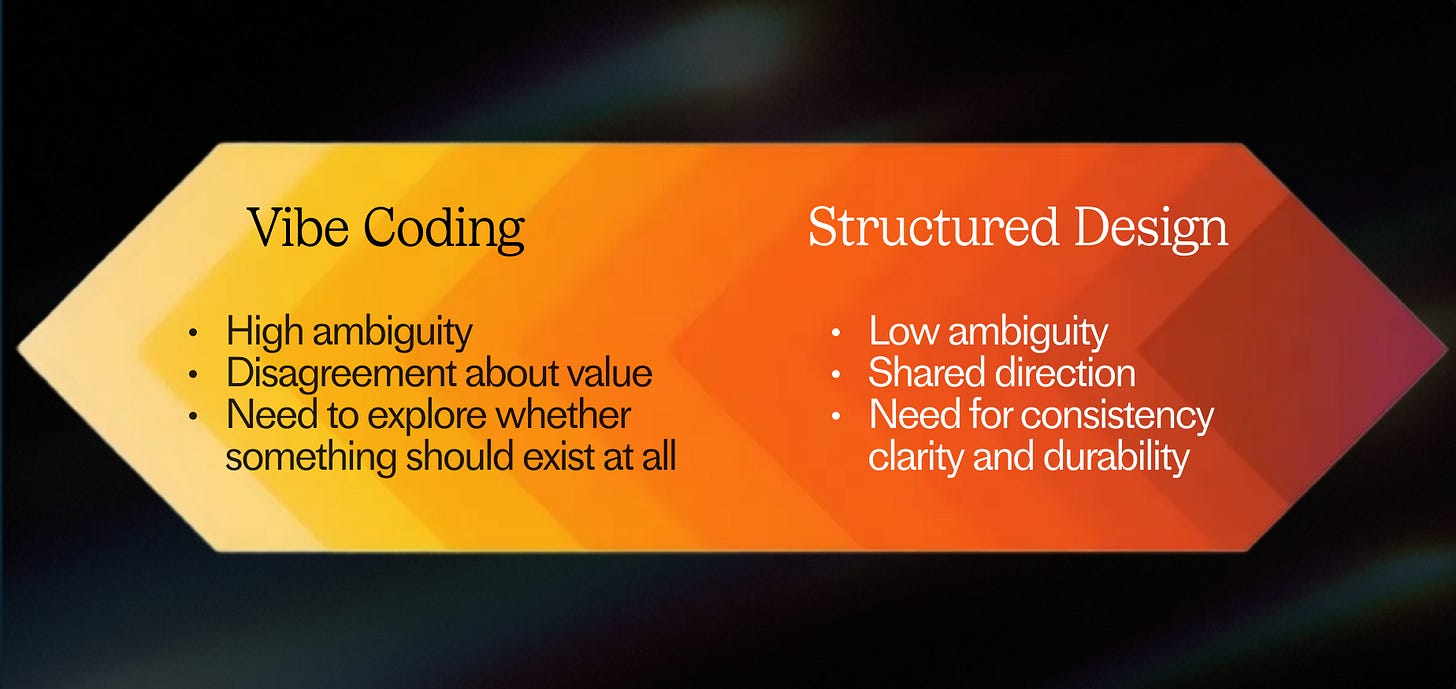

One of the biggest mistakes I see is treating vibe coding as either a default or a novelty. In reality, choosing when to vibe code is becoming a new dimension of design judgement.

Some work benefits from early structure. Other work suffers when defined too soon, especially when it depends on timing, behavior, real data, or interaction.

This is why it’s useful to think about design work on a spectrum:

Most work should move from left to right over time. Starting on the right too early leads to premature rigidity. Staying on the left too long leads to chaos.

Vibe coding doesn’t replace structured design work—it precedes it. Its job is to collapse ambiguity, not to carry ideas to the finish line. Once direction is clear, the work still needs the rigor of systems thinking, accessibility, and careful specification. Knowing when to switch modes is the skill.

A Hard-Earned Lesson

One of the clearest examples came from a data-heavy insights product I worked on last year. Leadership was fixated on a specific visualization from an early vision deck. I suspected it would be overwhelming with real data, but abstract arguments weren’t changing their minds.

So, I made the question explicit. I put together two versions of the experience using real customer data: one aligned with my direction, one aligned with the requested visualization. In context, the vision-era version was overwhelming and difficult to parse. Users struggled. The concern stopped being theoretical.

Those prototypes didn’t ship. But they did their job.

That moment worked not because the prototypes were impressive (they obviously weren’t) but because it was the only way to answer a question that debate couldn’t resolve. It helped me realize that vibe coding isn’t a default step, but a specific tool for specific moments. I’ve since narrowed down to four signals that tell me it’s time to switch modes.

When to Vibe Code

Vibe coding is most valuable when progress depends on making something real enough to react to.

1. When the value proposition is uncertain

When value is uncertain and debate replaces experience, the real question isn’t how to build something but whether it should exist at all.

Abstract ideas keep teams arguing in circles. Vibe coding breaks that loop by making the experience tangible, proving or disproving value fast.

A great demonstration of that happened with a prototype of a new agentic assistant to help customers build complex automated procedures for Fin. After weeks of existential argument, my colleague James Cash vibe prototyped an agentic experience that convinced our team to dedicate resources the very next day after it was shared.

Many “value” debates stem from people picturing different versions of the same idea, and static mocks only make that confusion worse. An interactive prototype, especially one grounded in realistic data, collapses those interpretations into a shared reality. Designers often underestimate how much unrealistic data distorts feedback. For intelligent or data-heavy features, realistic data is a must.

2. When feasibility or scope is unclear

Sometimes the question isn’t whether something is valuable—it’s how much of it is necessary.

When it’s unclear whether removing a capability would break the experience, or when engineering effort feels hard to estimate, vibe coding can help. By incrementally simplifying or stripping things back, you can feel where the experience becomes incomplete.

This is often faster and clearer than debating scope in the abstract.

3. When the experience depends on things static tools can’t express

If time, motion, state, variability, personalization, or latency materially affect how something is perceived, static designs will only get you so far.

When behavior is key to the product, a vibe prototype is the new wireframe.

For instance, we’ve been experimenting with new visual themes for Fin’s brand, and vibe coding has allowed our creative team to really push the envelope with amazing prototypes.

That vibe-coded asset soon became the Fin Voice site.

You can see what’s possible by looking at two more of ÌníOlúwa Abíódún’s incredible and hypnotizing prototypes: a light flare exploration and an interactive dot grid.

4. When alignment matters more than implementation detail

There are moments when what’s truly mission-critical isn’t how something is built, but how it feels.

In these cases, vibe coding can be an effective way to align with engineering without over-specifying the solution. A prototype can communicate intent, interaction, and tone—while deliberately leaving room for engineers to make smart implementation decisions.

This works especially well when:

You’re collaborating with senior engineers who can own details once aligned

You want to avoid premature constraints

Your goal is shared understanding, not a final spec

Done this way, vibe coding becomes a low-key collaboration tool that gives engineers autonomy while ensuring the experience doesn’t drift away from its core intent.

These situations all point to the same underlying pattern: vibe coding is most powerful when alignment is the real bottleneck. Not alignment on pixels or specs, but alignment on value, feasibility, and intent.

When used this way, it can quietly resolve disagreements that would otherwise drag on for weeks—without escalation, without over-specifying solutions, and without forcing anyone to “lose” an argument.

How to Vibe Code Without Causing Damage

Because vibe coding collapses ambiguity so quickly, it needs guardrails.

Highly effective vibe-coded prototypes can be small, disposable, and short-lived. They’re built to answer a specific question, not simulate a full product. If it starts to feel like you’re building infrastructure or polishing details that won’t survive production, you’ve gone too far.

Every vibe-coded prototype should answer one primary question. If you can’t name that question, the prototype will try to answer everything—and succeed at none of it.

If you can’t explain how the underlying system works, don’t share the prototype outside a small, trusted circle. The more real something feels, the more caveats it requires if you lack confidence in the underlying feasibility.

Vibe coding is great at surfacing questions, not just answers. If it reveals deeper UX or system problems, that’s success—not failure.

It’s also terrible at communicating failure modes on its own. Use it to demonstrate the experience, but rely on more structured artifacts to spell out edge cases, recovery, and safeguards.

And finally: don’t over-sell it. Be explicit about what the prototype answers, what’s incomplete, and what doesn’t exist yet. Expectation-setting is part of the work.

When It’s Time to Exit Vibe Coding

Vibe coding is successful when it makes itself unnecessary.

It’s time to move on when the core question has been answered, when feedback shifts from “Is this useful?” to “Can we polish this?”, or when partners need specificity to move forward.

It’s also time to exit if the prototype starts being treated as a commitment. Replace it with something explicitly finalized. That’s not backtracking—it’s responsible handoff.

If you’re optimizing the prototype instead of the product, you’ve stayed too long.

Closing Thought

Vibe coding isn’t inherently good or bad—it’s amplifying.

Used well, it replaces opinion with tangible experience and accelerates alignment. Used poorly, it locks teams into the wrong things too early. Treat it like any powerful design tool: use it deliberately, name what it’s for, and know when to put it down.

The designers who thrive won’t be the ones who vibe code the most.

They’ll be the ones who know when an experience needs to be felt—and when it needs to be slowed down, clarified, and made right.

Thanks for sharing this, Molly.

The good: helping narrow down the best times to leverage vibe coding

The bad: I accidentally got lost/hypnotized by that interactive dot grid for about 2 hours 😂

Agree 100%! Which tool do you use most often to vibe code?